Have you been bothered by lower back pain? Are you one of those who suffer lower back pain periodically, where it comes and goes but never fully recovers? If yes, then I would like to share a different perspective from the usual approach to help you all understand how the body works and how to look for the right treatment. And this applies to other muscular pains as well.

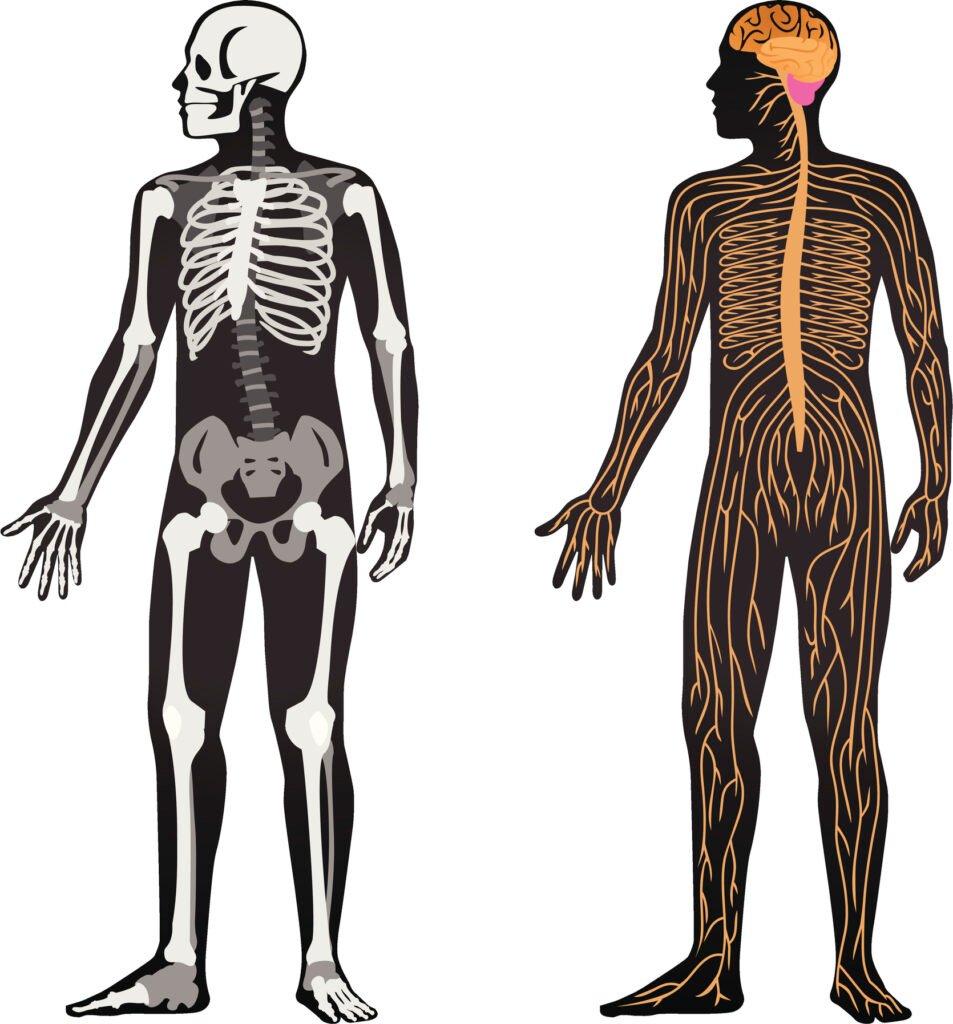

We know that to generate and control movement, muscles have to be activated and this can happen consciously or subconsciously. In this article, I would like to bring one system out of the shadows and into the limelight as there is not enough discussion on this system despite its importance – The Brain and the Nervous System.

First, let’s understand how the brain and the nervous system function. Basically we can more or less see it as how a computer would work. There are three parts to how the brain and the nervous system work: Input-Process-Output. We get stimuli through our senses, and those ‘data’ are sent to the brain via our nervous system; the brain then interprets those information so that it can send signals out to various body parts to respond accordingly – whether it is to move towards something, run away or to freeze.

In order for us to make sense of what is going on in our environment and engage with it meaningfully, we use 6 different senses (vision, hearing, smell, taste, touch and proprioception) to navigate and explore the world around us. And when it comes to movement specifically, the proprioception sense is very important because it allows us to keep track of where our body parts are in space, as well as in relation to one another.

As mentioned in my previous post (Movement Pattern & Motor Control), there are over 650 named skeletal muscles in the body and simple day-to-day movement such as squats requires coordination of multiple joints so that the action can be performed seamlessly. The brain is the conductor that orchestrates hundreds of muscles together to perform a desired movement successfully. Can you imagine how it would be if each instrument section in the orchestra plays at their own liking and rhythm for Serenade No. 13 for strings in G major? DISASTER!!

What happens when there is chronic, low-grade pain that niggles you every now and then? As we all know, pain is a protective mechanism. While it is not necessarily an absolute indication of how badly you have injured yourself, it sure prevents you from further ‘injuring’ the area that you experienced pain. That is why when we experience pain, most people tend not to move, with the intention of not wanting to aggravate the pain sensation.

However, there is a huge downside of adopting this approach when it comes to dealing with chronic pain. To have better insight into how the brain works when it comes to pain science, we have to go back to how the basics. Looking at it from a neuroscience lens, the brain’s main function is to decipher sense data so that it knows what to do next. Now, what happens when we stop moving? We stop sending stimuli to our brain via our proprioception sense. The lack of information diminishes the quality of perception, subsequently affecting the actions to be taken.

USE IT OR LOSE IT

So how does pain come into the picture? Well, let me ask you a question. What happens when you feel uncertain about things? You tend to be a little fearful, might be anxious, or worse case you might even freak out, right? That is what happens in the brain when it can’t be sure of where your body part is in relation to space and each other. And when it freaks out, the alarm system kicks in. That is where you experience pain, cautioning you to not make things worse by avoiding movement. Now you see how pain becomes chronic and the longer it stays, the more this vicious cycle repeats.

That being said, it is not easy to find the right balance between stimulating but not aggravating an injured area. I highly recommend those of you who are suffering chronic aches and pains to seek professional help. But in case that is not an option at the moment, my advice is to keep moving and work within a pain-free zone of the particular movement.

Next up, I will be covering what happens when the issue is at the processing station of the system. If you find this useful, comment below to let me know what your takeaway is.